Today, as we celebrate emerging artists in the Japanese ceramic scene, it’s essential to recognize the pioneers who came before them— hidden craftspeople whose stories deserve to be told and heard. Murata Gen, a master of his art, is one such artist whose remarkable pieces make a valuable addition to any ceramic collection. Murata Gen has been a favorite of Mingei collectors for decades, but his works have never received the recognition they deserve. Considered as the underdog of the Mingei folk-craft canon in the world of Japanese ceramics, Murata Gen’s works are underestimated, influential, and remarkable, all foregrounded by his training in classical painting. This exhibition aims to canonize him as an important part of Mashiko, Mingei, and Japanese folk-craft modern history.

What was the Mingei Movement? In the 1950’s Yanagi, Hamada and Kawai Kanjiro launched the Mingei movement where they were inspired by anonymous craftsmen. Yanagi validated Mashiko as a typical example of folk craft which epitomized and affirmed the category of Japanese folk-craft. From his experiences researching Western philosophical tenets and blending it with Japanese aesthetic philosophies, Yanagi constructed a “criterion of beauty” in Mingei, which was based on “the beauty of selflessness and anonymity.” This creed was inspired from his praise of a single object created by an illiterate, poor artisan called Minagawa Masu, who had been working for more than 60 years decorating sansui dobin (Tea pots with lids) with repetitive traditional patterns. His pots were unsigned, inexpensive, and ordinary kitchen items that lacked individuality.

Inspired by Minagawa’s traditionality rooted in Buddhist precepts of collective creativity, Yanagi’s Mingei was thus conceived as a set of antithetical concepts, such as anonymity or tradition in binary opposition to individual creativity. From these teachings emerged Murata Gen, a Mingei artist whose work seemed to subvert Yanagi’s movement towards a more rigid criterion of beauty in Japanese folk-craft. While creating pottery as a Mingei artist, Murata also began signing his pots and functional works, thus removing the notion of anonymity. This clashed with Yanagi’s ideological sensibilities. Yanagi, who subscribed to anonymous craft as the ultimate expression of Japanese folk craft values and cultural identity, disagreed with Murata’s attempt to expand his definition.

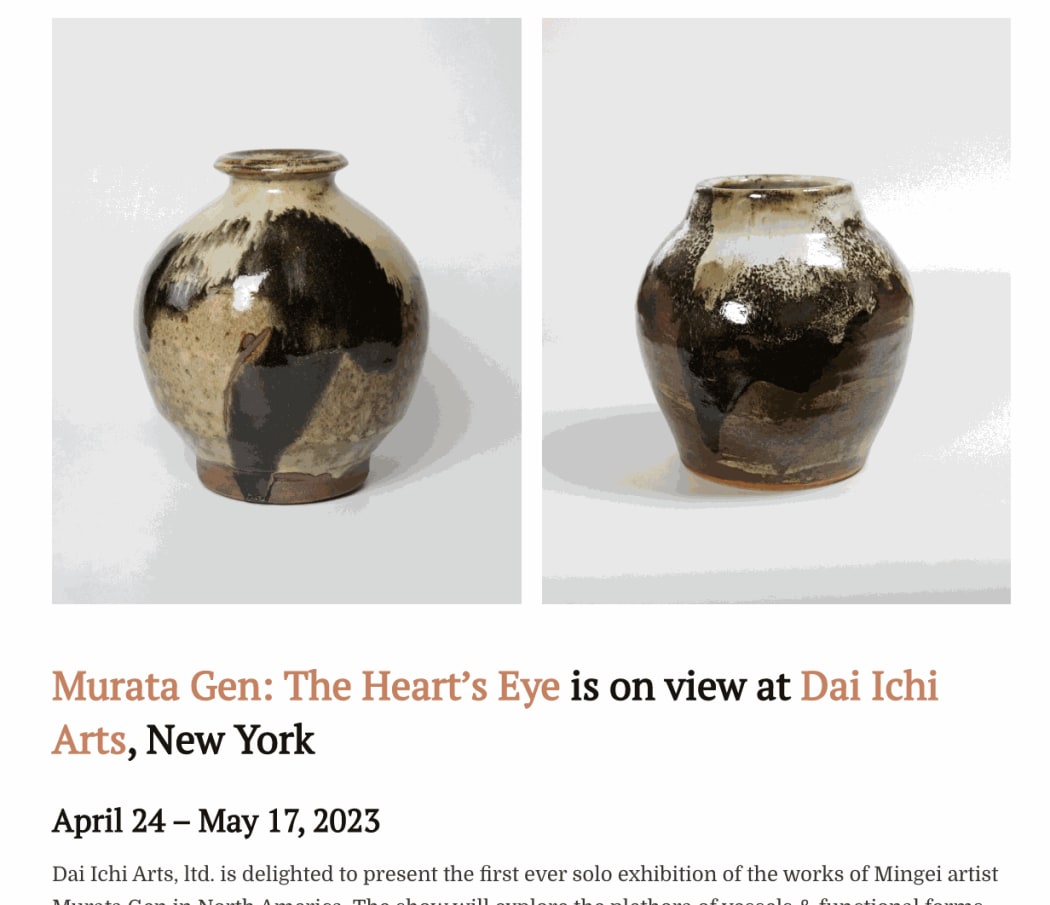

Born in 1904, Murata studied painting at the Kansai Bijutsu Gakuin (Kansai Art Academy). The onset of the first world war re-defined his career from painter to potter. After encountering Mashiko works in Tokyo, he followed in Hamada Shoji’s footsteps, whose Mingei pottery he greatly admired. He displayed his hard-earned honed skill and mastery over traditional glazes such as Nuka (rice-husk), kaki-yu (persimmon), and various tetsu-yu (iron glazes) that are displayed in a scrolling pattern over his functional clay wares.

Murata’s training in classical painting foregrounds his mastery over surface-scape. His functional wares employ unique glaze decoration to express scenic vistas. Like Hamada, Murata Gen chose to use only clay and glazes indigenous to Mashiko; he was a mindful Mingei practitioner that built his clay works with intention. However, he decisively departs from Hamada Shoji in choosing to use the exterior of his jars and bowls as, as it were, “canvases” to express his deeply-held artistic intentions.

It is not surprising, therefore, that he defined his profession as one which could marry the role of both potter and artist. Clay became his canvas. His sensitivity to the clay medium, which simultaneously drew upon his training as a painter, flourished, and Murata established himself firmly as a Mingei potter in his own terms.

Murata Gen mostly worked by himself and he always signed his work with a ‘む mu’ all his life. He sought to establish himself as an artist, blurring the lines between craftsmanship and high art. In doing so, he desired to elevate collective traditions of craft to the status of high art, which Yanagi saw as a misreading of Mingei. Essentially, he claimed that if an artist signed their work, then it didn’t qualify as Mingei. Murata was rejected largely from the group: Murata’s desire to incorporate authorship into the Mingei tradition, and desire to expand the definition of craft philosophy, led to his work being blacklisted from the Mingei collective by Yanagi himself. As a result, the sensitive, masterful works by this great artist and craftsman have been severely undervalued in the past. Murata Gen passed away in 1988, and is survived by his three children. His third son, Murata Hiroshi (b. 1941), is a potter and continues Gen’s legacy through his work in ceramic bran glazes, iron and sand glazes, and iron-glazed paintings.

Murata Gen’s work stands at the boundaries of Mingei. His work questions the definitions of the folk-craft category in Japan. This constant push and pull is at the forefront of contemporary discussions about the often fluid categorical lines between design, art, and craft.

Read the full featured article on Ceramics Now Magazine here