The word celadon is said to have originated in 17th-century France, inspired by the soft green ribbons worn by the character Céladon in the pastoral novel L’Astrée by Honoré d’Urfé (1627). European collectors adopted the name for the elegant green-glazed ceramics imported from China, and ever since, the term “celadon” has been used in the West to describe a broad range of jade-like glazes.

In Chinese, celadon is called qingci (青瓷), literally “blue-green porcelain,” while the Japanese refer to it as seiji (青磁). But in Japan, these subtle color differences are further refined: for instance, kinuta refers to the pale blue-green hue seen in Longquan ware modeled after a famous mallet-shaped vase, while mise denotes a particular celadon tone from the elusive Mise kilns. The actual shards from this kiln was only discovered in 1987.

Three works by Nakashima Hiroshi and Suzuki Sansei.

Three works by Nakashima Hiroshi and Suzuki Sansei.

Three Longquan celadon glazed ceramics from 12th, 13th, and 15th century China, permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

(Left) Vase with Dragon Fish handles, 12th-13th century, China. View the object here.

(Middle) Incense burner, 13th century, China. View the object here.

(Right) Vessel in the shape of ancient bronzes, 15th century, China. View the object here.

Celadon glazes first rose to prominence during China’s Eastern Jin dynasty (317–420) and reached their peak during the Song dynasty at the famed Longquan kilns in Zhejiang Province. Valued for their resemblance to jade- a stone long treasured in Chinese culture- celadon wares were prized both for their aesthetic refinement and technical difficulty. A good celadon glaze requires not only high-quality materials but also expert control of kiln atmosphere and firing temperature. Its signature soft surface, with a slightly matte sheen and tiny bubbles suspended in the glaze matrix, only reveals its true beauty after careful buildup of thickness before firing.

Detail, vessel by Nakashima Hiroshi.

Celadon jar by Nakashima Hiroshi showing the celadon surface craqueleur.

Celadon jar by Nakashima Hiroshi showing the celadon surface craqueleur.

When surveying celadon wares from both China and Japan, one quickly realizes that the term encompasses a surprisingly broad spectrum- from deep olive greens to pale icy blues. Though these glazes have been produced for nearly two millennia, it’s only in recent decades that scientists have begun to unravel the precise chemistry behind their signature hues.

Wikipedia offers a helpful summary:

That last point is key. As ceramic specialist Nigel Wood noted in his 2014 research (published in the Oriental Ceramic Society volume Collectors, Curators, Connoisseurs, 2021), the signature celadon hue results from a delicate interplay between two oxidation states of iron—and titanium plays a critical role in mediating this balance.

To put it simply:

-

Ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) tends to produce bluish tones

-

Ferric iron (Fe³⁺) leans toward yellow hues

-

The presence of titanium (Ti⁴⁺) helps convert Fe²⁺ into Fe³⁺, influencing the final color

This reaction can be summarized as:

Through controlled experimentation:

-

A glaze with 1.8% iron oxide and no titanium yields a pale blue celadon (Japanese seihakuji, Chinese qingbai)

-

Adding 0.1% titanium by weight produces a classic green celadon

-

At 0.5% titanium, the glaze shifts to a yellow-green or olive tone, typical of Yue ware celadons

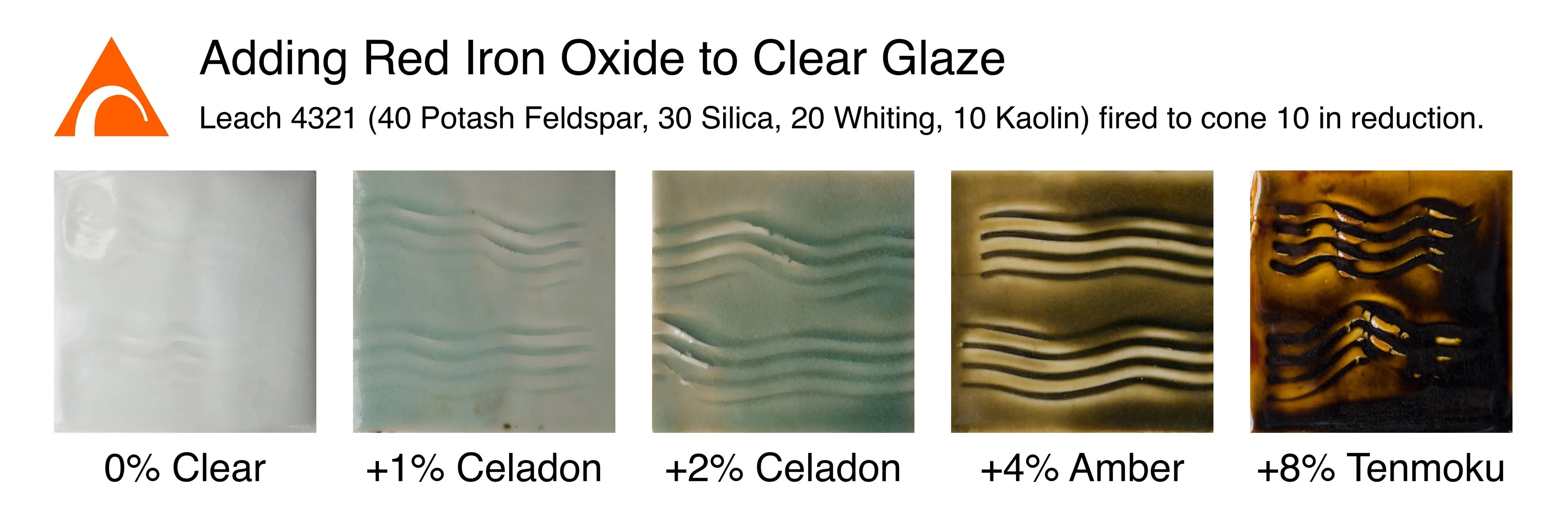

Images of various concentrations of iron oxide added to clear glaze, courtesy of Glazy. To view the glaze recipe for the above "Leach 4321," see their website here.

This subtle chemistry helps explain why “celadon” is both a specific and fluid term- less a singular color than a family of hues shaped by kiln atmosphere, mineral content, and firing expertise. The result is a timeless surface that continues to captivate collectors, potters, and scholars alike.