Before the modern era and the universalization of the color wheel, early Japan recognized four primary colors: red (aka), black (kuro), white (shiro), and blue (ao). Each held symbolic significance—red signified light (akari), black represented darkness (kurai), white conveyed clarity (shikkari), and blue embodied ambiguity or haze (shikkari shitenai).

Among these, blue (ao) evolved significantly in cultural and visual prominence. As an island nation, nearly every prefecture in Japan is connected to the sea, establishing blue as a natural constant in both the physical landscape and collective imagination. Over time, the language of blue became commonplace in artistic expression. This sensibility is especially evident in depictions of Mount Fuji, often rendered in blue tones to evoke atmosphere, distance, serenity, and the sublime. The practical and cultural significance of blue expanded with the introduction of indigo dyeing (ai-zome), brought to Japan through Chinese technological influence. Indigo (ai) became an everyday presence due to its affordability and deep, enduring hue.

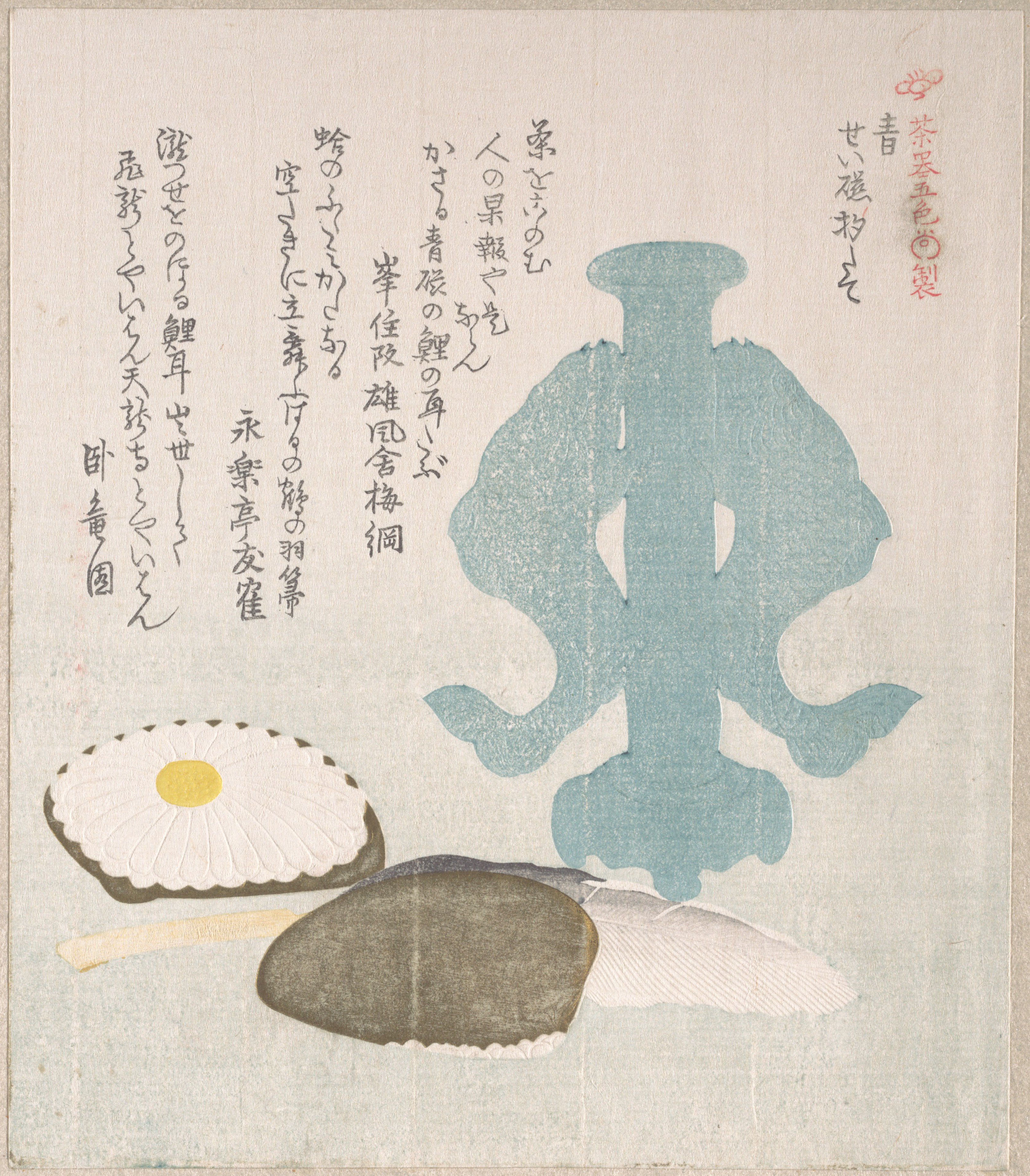

Eventually, certain blue hues in decorative expression—such as the distinctive blue-green of celadon ceramics—came to be associated with the elite, while indigo offered a deep, enduring, and accessible alternative for the general populace. As celadon gained popularity among high society, its unique tone of blue earned the name hisoku, meaning “secret color.”

Blue Dipper-holder of Celadon and Other Objects for the Tea Ceremony, Kubo Shunman (1757–1820), part of an album of woodblock prints (surimono); ink and color on paper, 19th century Japan. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. View the full image on the museum website here.

It is within this nuanced cultural context that Nakashima Hiroshi (1941–2018) emerges. A celebrated ceramic artist, he was designated a Living National Treasure in 2007 for his mastery of celadon ware. His commitment to the tradition of celadon was both personal and historically rooted. After becoming independent from his family kiln, Nakashima established his own studio in the mountains of Yumino City, Saga Prefecture. Surrounded by the remnants of historic kilns, he would often discover ceramic shards on his walks. These fragments revealed an astonishing diversity of forms, colors, and glazes. During one such walk, he picked up a piece glazed in a luminous green-blue hue. That moment marked the beginning of his journey into celadon. Soon after, he began studying Chinese celadons held in collections in Japan and Taiwan. He was taken by their depth, subtlety, and elegance.

For Nakashima, the glaze also served as a point of origin. Color frequently guided form. “For me, whenever the glaze leads, the shape emerges from it. Color becomes the priority,” he would say of his celadon-making process. He elaborated: “Sometimes the glaze would be scratched away, revealing the brown clay beneath to create contrast. Other times, layers of glaze were applied to a single form, evoking a dreamy world. These moments happened naturally and often, and in those moments, I grasped the beginning of a new way of creating celadon." His forms draw inspiration from Chinese bronze vessels of the Han and Tang dynasties, which he studied extensively in the national collections of Japan, China, and Taiwan. These influences are evident in the monumental scale, balanced proportions, and refined silhouettes of his work. Each celadon tone is chosen deliberately to match the form, a feat of precision and restraint, especially given Celadon's reputation as a notoriously difficult glaze to control.

Gui vessel (bowl-shaped ritual bronze vessel with lugs), bronze, brass, and copper, Shang dynasty. Image courtesy of the Palace Museum. View the object here.

His glazes are historically and technically grounded in Chinese Song dynasty celadon, yet Nakashima brought a contemporary sensibility to their application. He exploited the thick viscosity of celadon to create a sensuous surface texture. Under shifting light, his vessels reveal an undulating and luminous landscape: the craquelure pattern transforms their sea-green surfaces into shimmering shades of ocean blue. This textural sensitivity, achieved through meticulous firing and glazing techniques, adds an ethereal depth to his ceramics.

Nakashima Hiroshi, incense burner and jar with celadon glaze. Image courtesy of Dai Ichi Arts.

Despite his technical mastery and national recognition, Nakashima chose not to take on apprentices. He believed that the spirit of discovery should come from within. When young potters asked technical questions that were once considered taboo in his own training such as, “What kind of clay is this?” or “What is the recipe for this glaze?” It troubled him. To Nakashima, such inquiries stripped away the mystery and joy of making. Instead, he encouraged observation and intuition. Learn by watching, he believed. The rest must come from one’s own experimentation and inner curiosity.

Form and glaze both demonstrate the high degree of technical and aesthetic control that defined Nakashima’s practice. Managing celadon with this level of specificity is a rare achievement. His works set the high standard for preserving this refined tradition in Japan. It is this mastery, coupled with his fiercely independent and intuitive approach, that earned him the title of Living National Treasure.