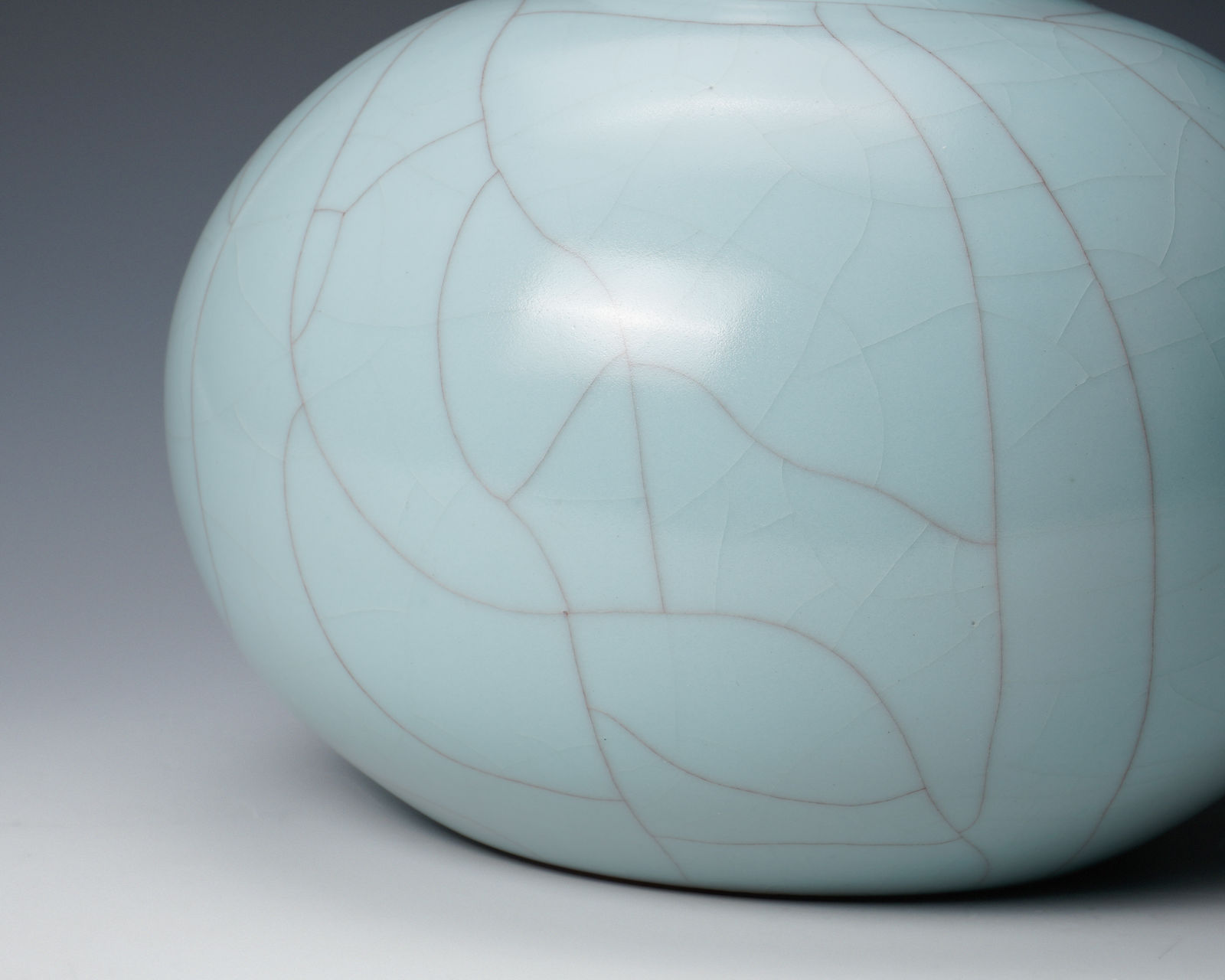

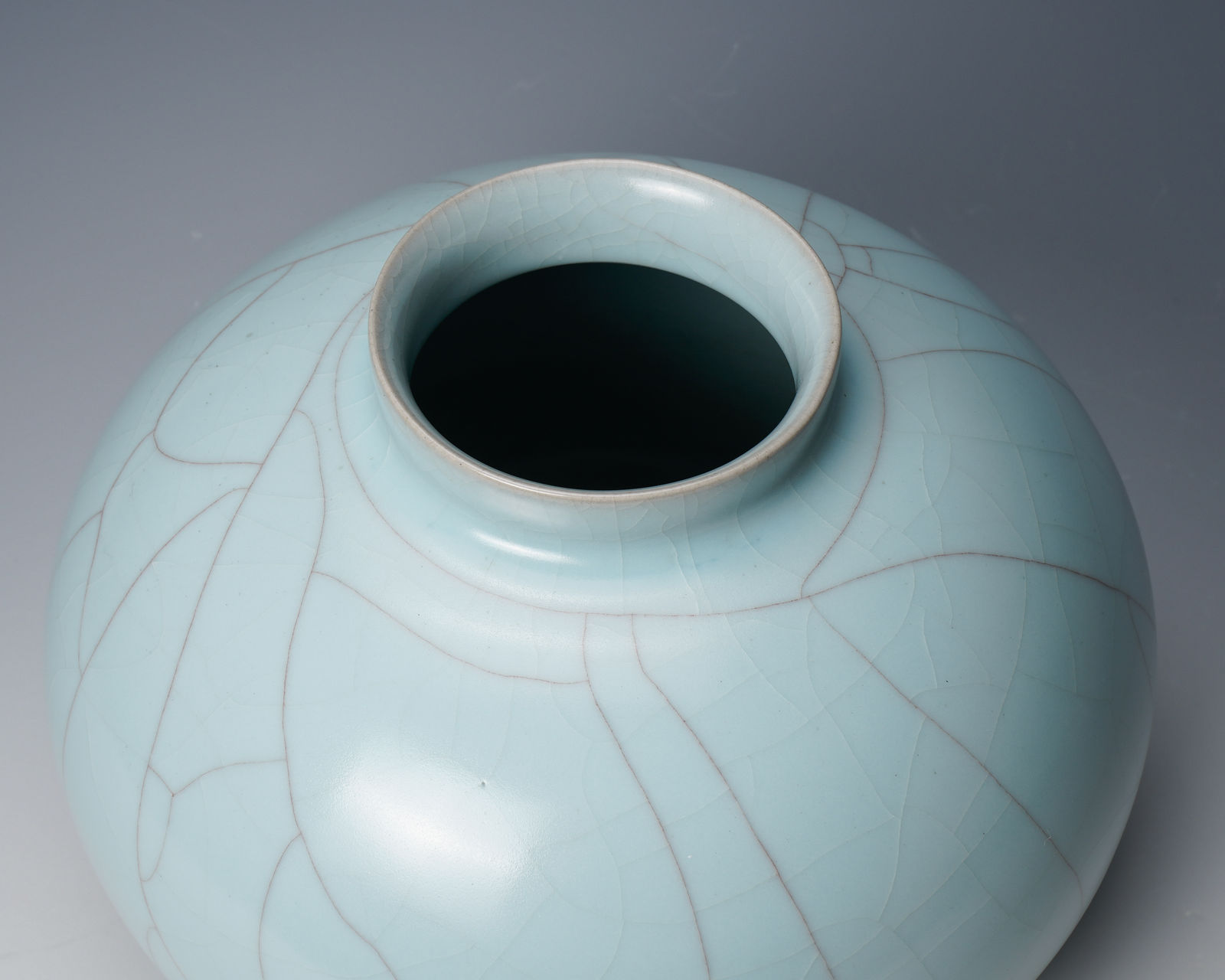

SUZUKI Sansei 鈴木三成 b. 1936

H16.5 × Dia 21.8 cm

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

This vessel showcases Suzuki Sansei’s distinctive “Guan” crackle pattern- a hallmark of a type of highly prized Song dynasty ware from the Jiaotan kilns in ancient China- is achieved through a deliberate manipulation of materials: the glaze is formulated to contract more than the clay body during cooling, causing it to fracture and reveal the dark clay beneath. The technical achievement showing a careful understanding of surface and glaze structure gives his vessels their compelling visual depth.

A dedicated student of Chinese Longquan wares and Southern Song celadon, Suzuki Sansei honed his mastery of celadon glazes, skillfully exploring their full chromatic potential. From cool blues to warm sea greens, his technical precision and sensitivity to glaze behavior set his work apart, capturing both the refinement and spirit of the Chinese tradition he draws from. Suzuki trained under the celebrated Kawamura Seizan 河村 蜻山 (b. 1890) at his Kamakura Kiln, before going on to build his own kiln in Kanagawa prefecture. Kawamura’s influence on Suzuki’s work is palpable in both their commitment to bringing traditional Chinese techniques to contemporary light, as well as the appreciation for subtle and muted aesthetic sensibilities.

Centuries earlier, Song dynasty potters discovered that when glaze and clay shrink at different rates during firing, the resulting tension produces fine networks of crackles. Far from a flaw, this effect was cultivated for its beauty. In making such ceramics, Song artisans would often apply multiple layers of glaze, using a series of controlled firings (including a final high-temperature firing followed by a carefully managed cooling phase) to achieve luminous surfaces veined with a coveted crackle. In the case of Guan ware, these patterns were often accentuated by the use of dark clay bodies or the staining of cracks to heighten surface contrast and visual appeal.

Suzuki Sansei is among a select group of contemporary Japanese ceramicists, alongside celebrated potters like Nakashima Hiroshi and Kawase Shinobu, who have studied and revived the complex techniques of Southern Song Guan ware. Originally produced under imperial patronage after the Southern Song court relocated to Hangzhou in the 12th century, Guan ware emerged from kilns such as the renowned Jiaotan kiln, which produced refined stoneware with thick, glassy glazes over delicate bodies. These wares, with their subtle hues and captivating crackle surfaces, represented the pinnacle of technical and aesthetic achievement. Today, that legacy lives on in the hands of artists like Suzuki Sansei, who reinterpret and reimagine these traditions for a contemporary audience.